Useful Laws of the Land

The most important ideas are those that apply to multiple fields.

A discovery from one field that’s useful to another field likely uncovers a truth about how people think and behave. And figuring out how people think and behave is the most important part of most fields.

Here are eight laws from all kinds of fields that should be useful regardless of what field you’re in.

1. Okrent’s law: “The pursuit of balance can create imbalance because sometimes something is true.”

Journalist and author Daniel Okrent once commented on the problem of journalists giving equal weight to fringe views with little evidence in the name of appearing balanced, which can give fringe views credibility and cause imbalance. He said:

The problem is real, and pervasive, and getting more complicated. As fewer and fewer news media stake a claim on being impartial, those that do are more and more inclined to cover their asses with the “on the one hand, on the other hand” trope. Depresses the hell out of me.

Being open-minded is an asset at one level, a liability at another, and eventually a catastrophe. This is true in many fields.

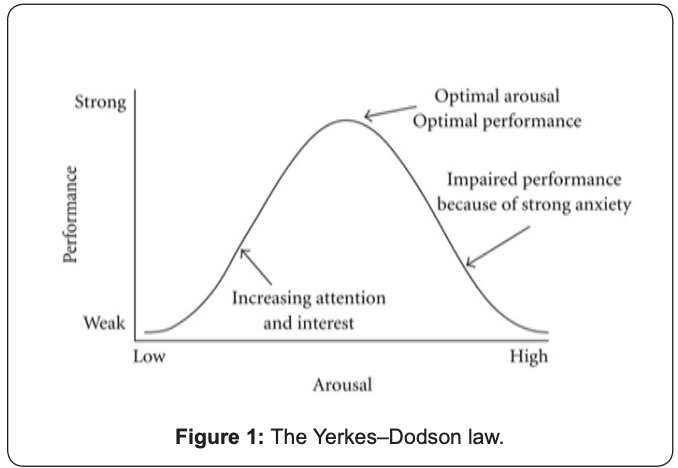

2. Yerkes-Dodson Law: Performance increases with anxiety and excitement, but only to a point.

Formed by psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson in the early 20th century, it looks like this:

At one level, excitement increases attention and helps you focus. At another higher level, you choke.

Highly relevant to incentives, I think of the Yerkes-Dodson law in investing, where the rewards for being right can be so high that smart people fumble their ability to manage risk in ways they never would when dealing with smaller, less exciting, rewards.

3. Vierordt’s law: We underestimate long periods of time and overestimate short periods of time.

Nineteenth-century physiologist Karl von Vierordt spent most of his career studying how people perceive time. His biggest finding is the opposite of what you’d assume.

Make someone wait in a room for one minute. After a minute, ask them how long they think they’ve been waiting. They’ll likely tell you something like “three minutes.” Now put them in the room for an hour, and ask them again. They’ll likely tell you something like “40 minutes.”

The longer something drags on the easier it is to forget the earlier moments of your experience. Five minutes can feel long because you remember everything you’ve thought about over those five minutes. An hour can feel short because your mind might have contemplated 17 different topics during that period, 15 of which you don’t recall anymore.

Vierordt had no interest in business, as far as I know. But let me propose the investing version of his law: Compounding is hard because a bad month can feel longer than a good decade.

4. Cunningham’s law: The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question. It’s to post the wrong answer.

Coined by programmer Ward Cunningham, it’s familiar to anyone with an active social media account.

People like to fight online more than they like to help. They’re quicker to point out flaws than to become a friendly resource. I don’t want that to be true, but experience tells me it is.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt wrote last month:

If you constantly express anger in your private conversations, your friends will likely find you tiresome, but when there’s an audience, the payoffs are different—outrage can boost your status. A 2017 study by William J. Brady and other researchers at NYU measured the reach of half a million tweets and found that each moral or emotional word used in a tweet increased its virality by 20 percent, on average. Another 2017 study, by the Pew Research Center, showed that posts exhibiting “indignant disagreement” received nearly twice as much engagement—including likes and shares—as other types of content on Facebook.

The internet promotes the same dynamic as road rage: once you’re arguing with a computer (or vehicle) rather than a person, social norms vanish.

5. Parkinson’s law of triviality: the amount of attention a problem gets is the inverse of its importance.

Laid out in historian Cyril Parkinson’s book Parkinson’s Law, which wrote:

“The time spent on any item of the agenda will be in inverse proportion to the sum [of money] involved.”

Parkinson described a fictional finance committee with three tasks: approval of a $10 million nuclear reactor, $400 for an employee bike shed, and $20 for employee refreshments in the break room.

The committee approves the $10 million nuclear reactor immediately, because the number is too big to contextualize, alternatives are too daunting to consider, and no one on the committee is an expert in nuclear power.

The bike shed gets considerably more debate. Committee members argue whether a bike rack would suffice and whether a shed should be wood or aluminum, because they have some experience working with those materials at home.

Employee refreshments take up two-thirds of the debate, because everyone has a strong opinion on what’s the best coffee, the best cookies, the best chips, etc.

The world is filled with these absurdities. In personal finance, Ramit Sethi recently said we should stop asking $3 questions (should I buy coffee?) and ask more $30,000 questions (should I buy a smaller home?). Most people don’t, because it’s hard and intimidating. In any given moment the easiest way to deal with a big problem is to ignore it and fill your time thinking about a smaller one.

6. Chekhov’s gun: remove everything from writing that doesn’t need to be there.

Novelist Anton Chekhov wrote:

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”

Make your point, make it clear, and get out of the reader’s way.

7. Campbell’s law: social measures of performance distort the performance of the thing you’re measuring.

Psychologist Donald Campbell wrote in 1976:

Achievement tests may well be valuable indicators of general school achievement under conditions as normal teaching and good general competence. But when test scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.

Don’t miss the double disaster here: it’s not just the test scores that lose relevance; the teaching also gets worse when test scores are valued because the curriculum becomes optimized for testing rather than learning.

The strangest example of this is when Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were caught systematically underreporting their earnings, purposefully stalling business and pushing potential earnings into future quarters in order to make earnings appear less volatile. Incentives are wild creatures.

8. Benford’s law of controversy: “Passion is inversely proportional to the amount of real information available.”

The line appeared in science fiction author Gregory Benford’s book Timescape.

Data has a way of keeping excitement in check, whereas if you have to take a leap of faith on something you’re likely to leap as far as your mind allows.

The median income of the people of another state: data I can confirm and everyone can agree on.

The feelings and political beliefs of the people of another state: no way for me to easily tell. But I can guess and draw conclusions, some of which are wrong and missing content, and might anger me, which angers them, and so on.

Former Netscape CEO Jim Barksdale once said, “If we have data, let’s look at data. If all we have are opinions, let’s go with mine.”

He wasn’t serious, but it seriously explains a lot of things.